Why Aesthetics Should be Medical, NOT a Beauty Trend

It shouldn’t be complicated or controversial to say that a medical specialty should be medical. Unfortunately, in this case, it sometimes is.

Aesthetic medicine is exactly that - a medical specialty. Also known as non-surgical cosmetic medicine, at started as a niche most strongly associated with plastic surgery and dermatology and has exploded into its own specialty in its own right.

Unfortunately, lack of regulation in the UK has trivialised this specialty, and while it clearly is related to beauty, it is vitally important that it is understood to be completely distinct and separate from beauty. Medical aesthetics treatments are NOT beauty treatments.

Don’t get me wrong. Beauty treatments can are amazing and beauticians can be artists. Beauty treatments, make-up, fashion - these all follow trends that are influenced by place, time, and culture.

Medical treatments should not be based solely on trends.

This is how you cause extreme distortion and have treatments that clearly aren’t in the patients’ best interest. Puckered skin and over-filled faces with no respect and often no understanding of natural anatomy or the physiology of ageing. Serious body dysmorphia can result or even be worsened.

When you’re using prescription medications and medical devices, risking complications and side effects with potential serious complications, ethically - as a clinician - you cannot be chasing trends.

Let’s see some of the fascinating beauty trends in history, including harmful ones that illustrate why it can be dangerous to chase a trend.

The Most Fascinating Beauty Trends in History

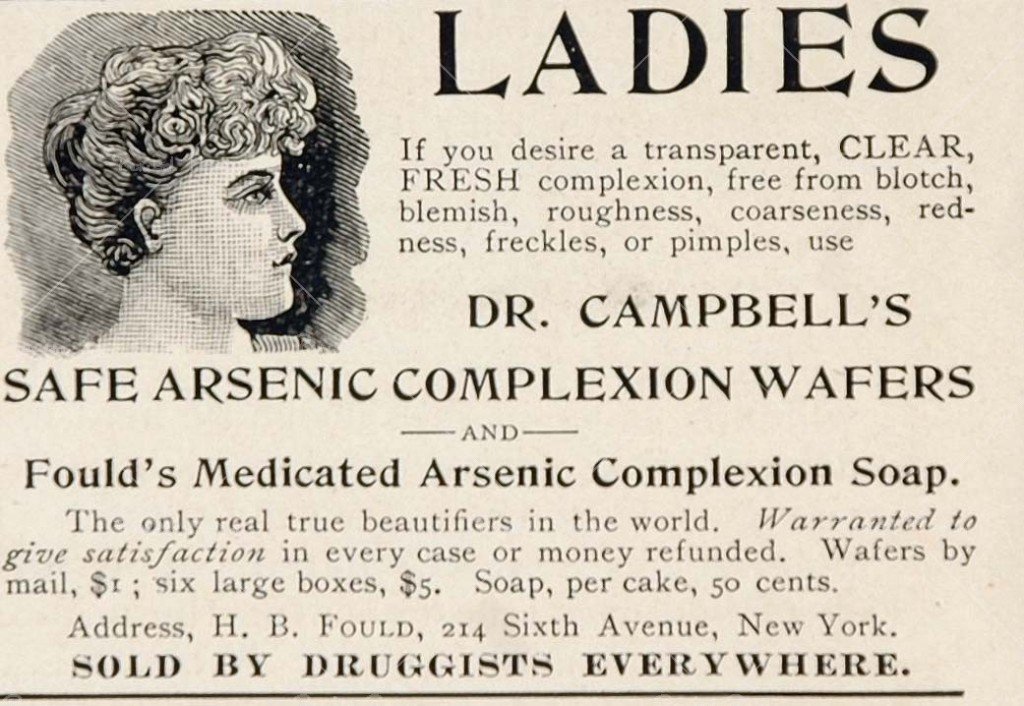

Arsenic Wafers, and Lightening Skin with Lead and Mercury

For many years, pale skin was a sought after beauty trend. It signified wealth and privilege - essentially it told the world that you did not work and that you were not a labourer under the sun. Hats, gloves, and umbrellas were used to shield women from the sunlight.

Women would swallow tablets containing arsenic. They would use makeup containing lead and mercury. Queen Elizabeth I famously painted her face in lead - a pursuit of a beauty trend that may have led to her death.

Mercury-containing creams were effective, like the ones touted by non-medic charlatan Anna Ruppert, but lethal. Today, skin-bleaching and colourism continue to be a problem in the world of beauty. While an effective and safe ingredient when prescribed and used as directed by a doctor - there are serious health implications associated with the misuse of hydroquinone.

Bloodletting

The obsession with looking pale even extended as far as deliberate anaemia! Bloodletting was a common practice in history to treat a variety of medical ailments. We know now that it did not have any benefit in curing diseases. In the Victorian era, it was used to promote a pale appearance.

A small incision was made in the arm, and the patient would squeeze a stick until enough blood had flowed from the wound and been collected in a bowl. This practice was commonly undertaken at a barber’s shop, and is what is behind the iconic design of the barber pole that we know today. The red of the pole signified the blood, and the white the bandages used to mop up the blood.

Belladonna for Sparkling Eyes

Woman with a Mirror by Titian

Belladonna translates to “beautiful woman” in Italian. Sparkling, dark eyes were the height of beauty in the Renaissance. How as this accomplished? By using belladona extract from the deadly nightshade - one of the most poisonous plants known to man!

In modern medicine we use the active compound in belladonna - known as atropine. It is a heart medication with the potential to cause serious arrhythmias. It works as an anticholinergic and blocks certain receptors in our nervous system. Use of this drug would make pupils dilate.

The root of the plant was collected and dried, and then placed into drops that could be applied to the eyes. Eyes looked large and bright, and were thought to appear more beautiful. While the effect was temporary, it came at the expense of blurred vision, light sensitivity, and a racing heart. Long-term use was thought to potentially cause permanent visual problems.

Renaissance Foreheads

Big, bald, beautiful foreheads were once all the rage.

Thought to signify youth and purity, women would pluck out their eyelashes, remove their eyebrows, and even plucked back their hairlines to achieve this look! The Renaissance saw a shift in beauty standards towards a more natural, unblemished appearance. A big forehead was seen as a sign of youth and innocence, as children often have larger foreheads before their facial features become more pronounced.

Artificial Cranial Deformation

The “Toulouse Deformation” seen in France in the early 20th century.

Artificial cranial deformation is a practice that has occurred in multiple countries for various reasons throughout history. Most recently, it was still happening in early 20th century France. This skull shape occurred due to the practice of bandeau amongst some of the French peasantry where they would tightly wrap a baby’s head to protect it.

Changing the shape of one’s head has occurred for a long time. While it had an extreme cosmetic effect, there is no evidence that there was any negative effect on brain development or cognition.

Some of the earliest examples of this practice was described by Hippocrates, who wrote of a group of people known as the Macrocephali (the “big heads”). He described how they considered the long heads a sign of nobility, and deliberately would bind infants’ heads at birth. The practice was also present in Mayan culture, where the higher someone’s status was in society the higher and more pointed their head shape would be.

Bound Feet

This infamous custom occurred in China where young girls’ feet and were broken and tightly bound as a status symbol and sign of feminine beauty. The practice started amongst the court dancers and the elite, but gradually spread throughout society. In the early 19th century, most upper-class women would have their feet bound.

This was obviously an extremely painful process, and would cripple these women, making it difficult to walk. Unfortunately, this was part of the appeal of the process and the so called “lotus gait” described a swaying walk with tiny steps that was meant to be irresistible to men.

Final Thoughts

Some of these beauty trends have social and cultural significance. Some are intriguing. Some are arguably mutilating.

The point is that pure beauty treatments or body modifications are outside the practice of medical aesthetics. Wandering into this area is not what clinicians should do. Equally, medical aesthetics is completely outside the scope of those without medical training.

This is why it is important to go to someone ethical and medically trained when undergoing aesthetic treatments. Clinicians need to ensure that any treatment we undertake is benefiting a patient physically, psychologically, and emotionally. If a treatment fails to meet any of these three criteria - as many of the above beauty trends do, then an ethical clinician cannot perform a treatment.

In 1933, a shocking exhibit toured America, displaying products that had blinded women, caused permanent hair loss, and even killed unsuspecting consumers. The "American Chamber of Horrors," as it came to be known, featured genuinely toxic cosmetic products, that contrast sharply with how remarkably safe modern products actually are.

Yet somehow, in our era cosmetic safety and regulation, we've developed an irrational fear of "chemicals" and "toxins" in beauty products. The irony is striking: we've never been safer from cosmetic harm, yet we've never been more frightened of our makeup bags.

Let's explore how the real horrors of unregulated cosmetics led to the robust safety framework we have today - and why most modern "clean beauty" fears fundamentally misunderstand how cosmetic regulation actually works.