Botched!: The Most Famous Cosmetic Medical Complications in History

Cosmetic medicine and the art of injecting fillers and toxin is a new, modern invention right?

Well - yes and no! While the use of hyaluronic acid and Botox are definitely new and modern - and our understanding of technique, anatomy and medical management has come a very long way - people have been having cosmetic procedures for as long as it’s been possible to do them.

But as long as there has been medicine, there have been complications.

I love medical history, and you can view these stories as fascinating cautionary tales from the past. If you look at any medical or surgical specialty in its infancy, you will always find mistakes and challenges along the way. None of the techniques, procedures, or materials described in this article are used today. In modern and medically-trained hands, these are not stories to be repeated!

The First Fillers

The first dermal fillers were very different from what we use today. Paraffin wax, a substance distilled by a German chemist in the 1830s, was known to be very inert (non-reactive), and therefore hopefully safe to put in the body. (Spoiler alert: it was not.)

Paraffin was first documented to be injected for cosmetic purposes by Dr. Robert Gersuny, an Austrian surgeon. It was used to create testicular prostheses for a patient who had suffered tuberculous epididymitis, and had to have his originals removed. (Aesthetic medicine is so glamorous, right?)

The method of paraffin injections typically consisted of injecting hot, liquid paraffin wax and then molding it into the desired shape.

From there, paraffin use for aesthetic medicine increased, but not without consequences!

John Humphrey Woodbury (1851-1909)

We all love a self-made man, but there might be such a thing as a little too self-made. Enter John Humphrey Woodbury, a very complex man, who self-styled himself as a dermatologist and surgeon. The story goes that he had a large mole on his face throughout his adolescence which, when finally removed, dramatically improved his self-esteem (maybe a bit too much - as he decided he would then become a doctor without bothering about the medical degree). This inspired him to help others by starting his own medical practice of dealing in beauty products and aesthetic medicine. Perhaps he had good intentions, but this all led to a great deal of (you guessed it) complications.

Woodbury did have enormous initial success, pioneering a number of treatments in the cosmetic world. But he was also riddled with lawsuits for practicing without a medical license and malpractice (as well as one for “disorderly conduct for parading around scanitly clad” - my personal favourite).

In the end, the Woodbury Dermatologic Institutes went bankrupt and Woodbury himself had a sad end committing suicide in 1909.

Rosa Travers, the homeliest girl in New York (1924)

In 1924, the Daily Mirror ran the following advertisement in New York City.

A plastic surgeon has offered to take the homeliest girl in the biggest city in the country and to make a beauty of her. All you have to do is send your photograph with name and address to Homeliest Girl Contest Editor. We will not print names, and the photographs will be ‘masked’. Our art department will paint the masks on the photographs to obviate identification. Here is the chance for New York’s homeliest girl. Her misfortune may make a fortune right away.

The “winner” of this competition was Rosa Travers, a sweatshop worker, who underwent a number of early procedures in the realms of both surgical and non-surgical aesthetics. What happened to her after her treatments was never reported, which makes us think that it might not have been the major success that was hoped for. It was said that she had paraffin injections, and as our next poor lady will demonstrate, paraffin really was not what you wanted put under your skin!

Gladys Deacon, the Duchess of Marlborough (1881-1977)

One of the most famous dermal filler patients in history was Gladys Deacon, the Duchess of Marlborough. She was a beautiful French- American aristocrat, who won the hearts and and admiration of a countless number of men. Her beauty was renowned, and paintings of her famous blue eyes are still on the ceiling of the main portico at Blenheim Palace.

When she was in her 20s, she was unhappy with a kink in her nose, and decided to undergo paraffin injections. Unfortunately, she then became one of medical aesthetics’ most famous complications. The filler migrated to her chin, leaving her with unsightly “paraffinomas” in her face.

By this point in history, paraffinomas had been documented and described in the medical literature. They formed as the body reacted with inflammation to the foreign-body within it. Those injected with paraffin complained that they developed yellowish skin plaques at the site of injection, and there were even cases of emboli going to the brain or lungs.

The Duchess’s story ends sadly. Over the years, the paraffinomas became worse and reportedly migrated throughout her face. The once great beauty would not allow mirrors in her home, and died as a recluse.

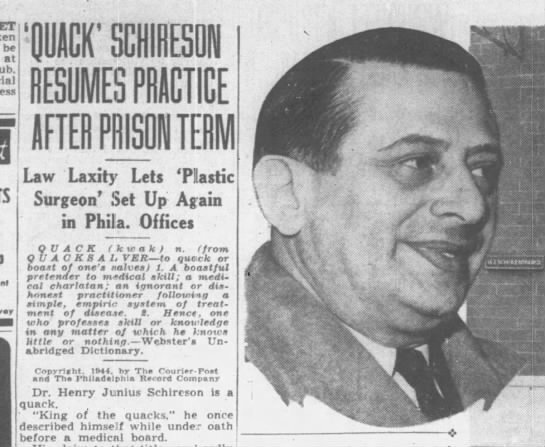

Henry Junius Schireson, King of the Quacks (1930s)

Henry Junius Schireson was one of the worst quacks to ever practice, another self-styled “doctor” with very little training. He had failed most of his medical school classes and was refused a license to practice medicine.

But he didn’t let that get in his way.

He was fame hungry and enjoyed doing things for publicity: including suing the famous beauty Lady Diana Manners for not paying for cosmetic treatments performed on her face (apparently an outright lie). He also claimed to have reshaped “It girl” Peaches Browning’s legs - also probably untrue.

His most famous, and horrific, complication occurred when a young lady came to him for help with a burn scar on her shoulder. He managed to convince her that he could improve the appearance of her legs, which he deemed not straight enough, and then attempted to perform surgery. He caused a gangrene that resulted in a real surgeon having to amputate the legs several weeks later in order to save her life. As the medical establishment exposed and ostracised him, he was forced to turn to other means to try trick patients into seeing him.

Apparently, Schireson would enjoy attending society parties to meet wealthy women, and would then send them gifts, including small dogs. He would convince them to come to his offices, where he could attempt all manner of cosmetic treatments. He was finally jailed (not for the first time) after all the complications he caused, and after having multiple suits for malpractice brought against him. He died penniless in the 1940s.

Las Vegas Showgirls (1950s & 1960s)

Fillers moved on from paraffin to silicone, but that doesn’t mean that there were no longer complications. Silicone was considered an equally inert alternative that could be used safely used for cosmetic procedures. However, similar to paraffin, these injections caused inflammatory reactions in the body - and sometimes the effects weren’t seen for years!

In the 1950s, Las Vegas was a wild and exciting town (probably not too dissimilar to today)! It was full of exotic nightlife, gambling, and Hollywood stars. The biggest entertainers of the era, including the Rat Pack, flocked to the city. And, of course, there were famous Las Vegas showgirls.

The showgirls would frequently get silicone injections to achieve the desired look of the time. This practice was referred to by the term, “Cleopatra’s Needle.” These injections went straight into the fatty tissue of the breasts (different from the silicone implants that would develop later), and sadly there would have terrible consequences for these young ladies. Sometimes it would take years for the complications to emerge - but when they did, the consequences were life-changing.

These were horrible inflammatory reactions: as one choreographer described: “The bubbles would start three years later…tearing apart their boobs - it was terrible.” The state of Nevada stepped in after seeing the consequences suffered by these women, banning liquid silicone injections.

Final thoughts

I love medical history, and you can view these stories as fascinating cautionary tales. If you look at any medical or surgical specialty in its infancy, you will find mistakes and challenges along the way.

But in learning about these incredible stories, I also appreciate how far we’ve come. The skill, safety, and artistry involved in aesthetics today is wonderful.

However, as much fun as I had in writing and researching this piece, it also really cemented the fact for me that we have come too far to have it be acceptable to have preventable complications be poorly managed in non-medical hands. Our patients deserve better. We’re no longer practicing late 19th or early 20th century medicine!

As much as I wish these types of stories about terrible complications were completely relegated to the past, they still happen today.

I have written about this before here, discussing the issues of regulation in the aesthetics industry in the UK. The lack of regulation here means that non-medical professionals can inject fillers as well as Botox, a prescription-only medication, despite this obviously not being best practice or even condoned by any of the medical companies, pharmacies or reputable trainers that distribute these products. These problems were highlighted by the government-commissioned Keogh Report in 2013, led by the medical director of the NHS. This review stated that there was clear a risk to public health and safety in allowing non-medical practitioners to deliver these treatments, especially in the case of dermal fillers.

So as fascinating as these stories are, you don’t want them to happen to you! Always check that your aesthetics practitioner is medically qualified.

Over a century ago, one fascinating case marked the dawn of cosmetic intervention as we know it today — and it involved paraffin wax.

In 1904, Dr. Benjamin T. Burley published a case report in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal detailing the use of paraffin injections to restore facial volume in a young woman suffering from bilateral facial atrophy.

This is more than just a curious footnote in the history of injectables — it’s a reminder of the human drive for aesthetic restoration, the early efforts to balance safety with innovation, and the long road we’ve walked from paraffin to the safe use of hyaluronic acid fillers today.